Briefing Paper: Reducing food system emissions in Brighton and Hove: Framing the challenge

Reducing food system emissions in Brighton and Hove: Framing the challenge

Guest post by James Joughin*

Brighton and Hove has been a pioneer on food policy. It has had a food strategy since 2006, and in 2020 was the first place to receive a Gold Sustainable Food Places award. There is much more to a food strategy than climate change, of course (Figure 1) – but as the Food Strategy Action Plan is being renewed, the question arises: what can a food strategy contribute to Brighton and Hove’s net zero ambition?

Figure 1

Source: https://bhfood.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Final-FULL-WEB-Food-Strategy-Action-Plan.pdf

How significant are the carbon emissions related to food and drink?

Globally, international research suggests that, in 2015, food-system emissions amounted to 34% of total global GHG emissions. For the UK, the independent Committee on Climate Change says that food systems account for over a third of UK CO2e emissions. The National Food Strategy 2021 says the food system accounts for a fifth of domestic emissions, with the figure rising to around 30% if we factor in the emissions produced by all the food we import (Figure 2) . It also provides a detailed breakdown of the contribution of food to GHG emissions by commodity (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2

Source: https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/

Figure 3

Source: https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/

For Brighton and Hove, there is no single figure. The Place-Based Carbon Calculator gives an average figure for greenhouse gas emissions related to food and drink of 1240 Kg of CO2e per person per year, which with a population of 290,000, would give a total of 360,000 tons per year. To this might be added the restaurant sector and the transport involved in last mile delivery (both driving to the supermarket and home delivery). Probably in excess of 500,000 tons a year is a reasonable estimate – at least 20% of the City’s total footprint.

As with other elements of the carbon consumption footprint, emissions very greatly according to income. The Place-Based Carbon Calculator gives a food and drink figure of over 2 tons per capita for Hove Park and Withdean, but only 639 Kg for East Brighton and 367 kg for Moulsecomb. These estimates are based on data for household income across different areas of the City.

It is worth noting that agriculture makes only a small contribution to Brighton and Hove’s territorial emissions: 10,000 tons in 2019, out of a total of 817,000. Nevertheless, the City’s 12,800 acre Downland Estate is a relevant resource. The Downland Estate Plan aims that the City Downland Estate will be carbon negative and climate resilient, its ‘biodiverse grassland landscape fully restored and teeming with wildlife’.

What can be done?

The Committee on Climate Change has made a number of recommendations related to food, especially diet and food waste. The Sixth Carbon Budget, covering climate policy up to 2037, called on the Government to

Implement policies to encourage consumers to shift towards healthier diets and reduce food waste, including:

• Low-cost, low-regret actions to encourage a 20% shift away from all meat by 2030 rising to 35% by 2050, and 20% shift from dairy products by 2030. An evidence-based strategy to establish options to successfully change behaviour and demonstrate public sector leadership.

• Measures are needed to reduce food waste by 50% by 2030 and 60% by 2050 with the public sector taking a lead through measures such as target setting and effective product labelling.

In its 2023 Progress Report to Parliament, the CCC noted that ‘a shift to low-carbon diets also brings co-benefits to the health of citizens.’

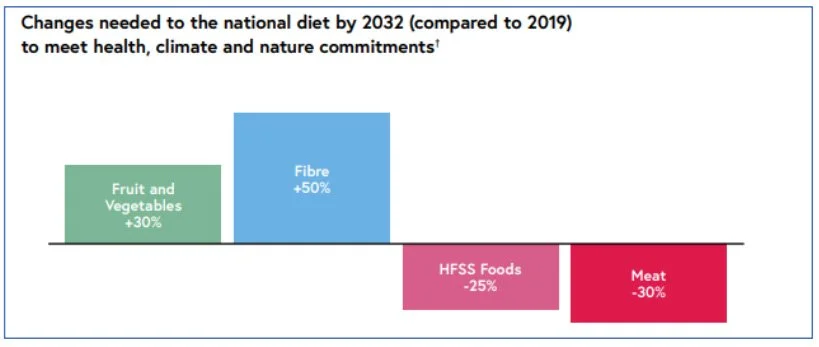

The Food Strategy made similar recommendations (Figure 5): a reduction in the consumption of meat and an increase in that of fruit and vegetables.

Figure 5

Source: https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/

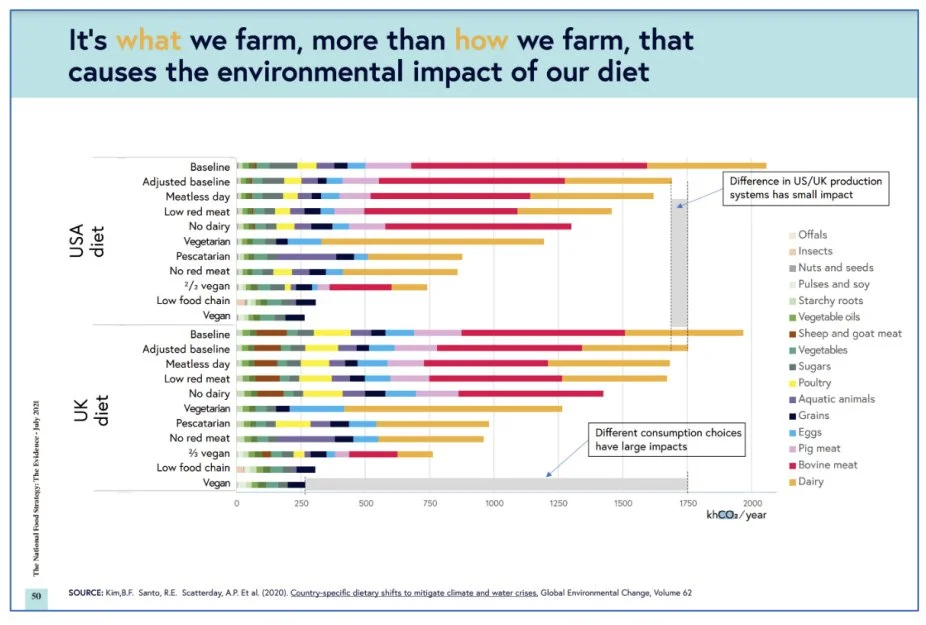

The Food Strategy also explored the impact on GHG emissions of different diets: reducing meat and dairy have a big impact on emissions (Figure 6). The food supply chain is complex and nuanced as it moves along each stage but the stand-out issue is that in beef and lamb production, emissions from animal feed production, land conversion, and methane production are very significant.

Figure 6

Source: https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/

For Brighton and Hove, the most recent action plans have focused on health and food poverty rather than the environment. However, the original Spade to Spoon strategy in 2012 listed reducing greenhouse gas emissions as one of eight key outcomes, with a focus on better farming practices, meat and dairy consumption, gases from food waste, and food transport. It said that

‘Our strategy addresses ways in which we can localise our food production and increase consumption of food produced from within a 50- mile radius, but only as part of a sustainable food system. The distance travelled by food, whilst significant, is not the only measure of food’s environmental impact, and factors such as the energy intensiveness of production and storage are amongst other crucial factors.’

Issues and options

There are multiple starting points, but the National Food Strategy, its message and its fate, is the most obvious place to start.

The NFS process was led by Henry Dimbleby. It was based on two years of research and in-depth consultations across the food and farming sector and was published in July 2021. Sir Partha Dasgupta, Frank Ramsey Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cambridge and author of The Economics of Biodiversity, described it as:

‘Analytically tight, empirically thorough, the Dimbleby Report is not only a masterly study of UK’s food problem, but it also constructs a framework wide enough to be deployed for studying the food problems societies face everywhere. The Report’s recommendations are detailed, convincing, and would be entirely implementable if we cared about ourselves and the world around us.’

In response to the Strategy, the Government released, a year later, a White Paper, its own ‘strategy’. Its key goals were listed as to:

· broadly maintain the current level of food we produce domestically, including sustainably boosting production in sectors where there are post-Brexit opportunities including horticulture and seafood

· ensure that by 2030, pay, employment and productivity, as well as completion of high-quality skills training will have risen in the agri-food industry in every area of the UK, to support our production and levelling up objectives

· halve childhood obesity by 2030, reducing the healthy life expectancy (HLE) gap between local areas where it is highest and lowest by 2030, adding 5 years to HLE by 2035 and reducing the proportion of the population living with diet-related illnesses; and to support this, increasing the proportion of healthier food sold

· reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the environmental impacts of the food system, in line with our net zero commitments and biodiversity targets and preparing for the risks from a changing climate

· contribute to our export strategy goal to reach £1 trillion of exports annually by 2030 and supporting more UK food and drink businesses, particularly small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), to take advantage of new market access and free trade agreements (FTAs) post-Brexit

· maintain high standards for food consumed in the UK, wherever it is produced

Many concerned parties were dismayed. Dimbleby himself was publicly critical saying the White Paper was

‘not a strategy. … It doesn’t set out a clear vision as to why we have the problems we have now and it doesn’t set out what needs to be done.’

The chief executive of Sustain, an alliance of some 130 ‘organisations and communities working together for a better system of food, farming and fishing’, Kath Dalmeny, said

‘The government food strategy looks shamefully weak…This isn’t a strategy, it’s a feeble to do list, that may or may not get ticked.’

Greenpeace UK’s statement was even more brutal:

‘By ignoring climate scientists and its own experts in favour of industry lobbyists, the government has published a strategy that, ultimately, will only perpetuate a broken food system and see our planet cook itself.’

There are still many ideas in the original report that can be pursued, however, and much information to be absorbed.

Another piece of the contextual jigsaw comes from the FAO Food and Climate National Action Toolkit, published after the COP28 in November 2023. This is unequivocal that the

‘overwhelming scientific evidence indicates that nothing other than the widespread transformation of food and agriculture systems is required to achieve the global climate change goals set forth in the Paris Agreement’ and that ‘accelerated action on food systems and agriculture’ is necessary. It highlights the need for ‘a more holistic understanding of agriculture – one that is not only a system for producing healthy food but also for ensuring healthy soil, biodiversity conservation, clean water, sustainable landscape management, and resilient livelihoods for communities’.

Of relevance to Brighton and Hove, the FAO report talks about

‘decoupling food production from fossil fuels’ and cutting ‘energy intensity in food systems; through reduced mechanization, lower use of fossil fuel-based inputs, shorter supply chains, reduced demand for meat, dairy and ultra-processed foods, and to some extent, increasing the uptake of alternative proteins (at least those which do not lead to additional greenhouse gas emissions)’.

Other actions suggested include a shift to renewable-based cooling (i.e., cold storage), heating (i.e., greenhouses) and drying technologies, and renewable energy for food processing and transport. There is also discussion about reducing and re-purposing food loss and waste and, of course, transitioning to more nutritious and healthy diets.

The Brighton and Hove Food Partnership has a campaign on Food and Climate Change, including an emphasis on better diet and on a circular economy, reducing food waste (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Source: https://bhfood.org.uk/resources/food-and-climate-change/

We should also not forget the role of the supermarkets. While their direct contribution to food system emissions is believed to be relatively low, the sector does have an important part to play (as well as opportunities to save costs). Supermarket emissions can be divided up as follows:

Scope 1: direct emissions from own operations

Scope 2: emissions from the generation of electricity and heat in products that supermarket’s purchase

Scope 3: emissions from agriculture, food processing, waste, and transport both upstream and downstream

Emissions from Scope 1 and 2 may be less than 10% of total but none of the supermarkets report comprehensively on Scope 3. Comparisons between supermarkets are not easy to make because they have different business models, which inevitably affect these comparisons – whether it is online-only Ocado, with more delivery-related emissions, or Iceland, which uses more energy for its freezers. However, Which has just a published a useful guide to the issues and it is clear that supermarkets have considerable capacity to push behaviour change in both suppliers and consumers.

Next steps

The priority is to support the Council and its partners in revising the Brighton and Hove Food Strategy. This will be an inclusive process and will necessarily involve many elements other than climate change.

From a climate perspective, it will be useful to improve the quality of data about the direct and indirect emissions associated with food and drink in the domestic, public and commercial sectors in Brighton and Hove. It will then be useful to try to build a consensus on how to move forward in integrating national climate goals into local food system issues, and to develop appropriate local ambitions. What are the links in the supply chain likely to offer the biggest/quickest gains? How can more funding for food system work be unlocked? And what lessons can be learned from elsewhere?

__________

Image: https://bhfood.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Final-FULL-WEB-Food-Strategy-Action-Plan.pdf

Perspective pieces are the responsibility of the authors, and do not commit Climate:Change in any way. Guest posts are published to explore issues or stimulate debate. Comments are welcome.